Что такое subdomain takeover

Subdomain Takeover, или как найти заброшенные поддомены

День добрый, сегодня, я хочу вам рассказать о перехвате поддоменов, какие утилиты я для выбрал для работы с этим и с помощью чего можно понять можно ли перехватить домен. (Спойлер: лучше руками).

Кому интересно, добро пожаловать под кат.

Утилиты:

Для себя я выбрал три утилиты, две из которых собирают данные из открытых источников, одна перебирает поддомены.

Утилита, которая может брутить, но ее брут меня не устроил, проверку в боевых условиях она не прошла.

Пример команды которую я использую для нахождения:

Удобный расширенный вывод, включая статистику по ip адресам.

2. SubFinder

Смысл утилиты такой же как и у amass, но другие источники данных и более высокая скорость работы.

Утилита которую я использую для перебора поддоменов, иногда генерирует массу false-positive результатов, часто доходит до 100к+. После нее перегоняю результаты самописным валидатором доменов и отсеиваю ненужное.

После сбора поддоменов и уникализации списка, надо получить CNAME записи и, если CNAME запись и ответ сервера совпадают, то попытаться перехватить поддомен, в этом нам поможет утилита — SubOver.

Так же вне зависимости от CNAME я вручную проверяю возможные адреса на перехват, для примера, поддомены у которых запись CNAME указывает на адреса *.herokuapp.com, *.cloudfront.com и тд.

Полный список сервисов в которых можно перехватить поддомен и ответы сервера для детекта возможности перехвата вы можете найти по данной ссылке.

Subdomain takeovers

A subdomain takeover occurs when an attacker gains control over a subdomain of a target domain. Typically, this happens when the subdomain has a canonical name (CNAME) in the Domain Name System (DNS), but no host is providing content for it. This can happen because either a virtual host hasn’t been published yet or a virtual host has been removed. An attacker can take over that subdomain by providing their own virtual host and then hosting their own content for it.

If an attacker can do this, they can potentially read cookies set from the main domain, perform cross-site scripting, or circumvent content security policies, thereby enabling them to capture protected information (including logins) or send malicious content to unsuspecting users.

A subdomain is like an electrical outlet. If you have your own appliance (host) plugged into it, everything is fine. However, if you remove your appliance from the outlet (or haven’t plugged one in yet), someone can plug in a different one. You must cut power at the breaker or fuse box (DNS) to prevent the outlet from being used by someone else.

How do they happen?

If the process of provisioning or deprovisioning (removing) a virtual host is not handled properly, there can be an opportunity for an attacker to take over a subdomain.

During provisioning

An attacker sets up a virtual host for a subdomain name you bought on the hosting provider, before you get to do it.

Suppose you control the domain example.com. You want to add a blog at blog.example.com, and you decide to use a hosting provider who maintains a blogging platform. (For «blog», you can substitute «e-commerce platform», «customer service platform», or any other «cloud-based» virtual hosting scenario.) The process you go through might look like this:

Unless the hosting provider is very careful to verify that the entity who sets up the virtual host actually is the owner of the subdomain name, an attacker who is quicker than you could create a virtual host with the same hosting provider, using your subdomain name. In such a case, as soon as you set up DNS in step 2, the attacker can host content on your subdomain.

During deprovisioning

You take down your virtual host, but an attacker sets up a new virtual host using the same name and hosting provider.

You (or your company) decide that you no longer want to maintain a blog, so you remove the virtual host from the hosting provider. However, if you don’t remove the DNS entry that points to the hosting provider, an attacker can now create their own virtual host with that provider, claim your subdomain, and host their own content under that subdomain.

How can I prevent them?

Preventing subdomain takeovers is a matter of order of operations in lifecycle management for virtual hosts and DNS. Depending on the size of the organization, this may require communication and coordination across multiple departments, which can only increase the likelihood for a vulnerable misconfiguration.

Subdomain Takeover: Ignore This Vulnerability at Your Peril

Management thinks that letting folks from WidgetCo log into widgetco.ourapp.com will really help make the sale. It seems harmless enough. But using a custom subdomain like this can open WidgetCo up to potential security issues. In this article, Julien Cretel introduces us to Subdomain Takeover attacks and discusses ways we can mitigate them.

Unsurprisingly, DNS is not immune to misconfiguration, and poor DNS hygiene opens the door to all kinds of abuse that can wreak havoc on the security of your organization and its stakeholders. Of course, if attackers gain access to your DNS configuration and are able to create records or modify existing ones,

However, attackers don’t need such a strong foothold in your system to cause harm. In some cases, a dangling CNAME record on one of your subdomains is all they need to take control of some (or all) of the content served by the subdomain in question. Such a security issue is known as a subdomain takeover.

In this post, I will do the following:

A Typical Scenario

You’ve just fallen victim to a subdomain takeover!

Why You Should Pay Attention

Subdomain takeover was pioneered by ethical hacker Frans Rosén and popularized by Detectify in a seminal blogpost as early as 2014. However, it remains an underestimated (or outright overlooked) and widespread vulnerability. The rise of cloud solutions certainly hasn’t helped curb the spread.

In many ways, subdomain takeover is an insidious security issue:

Impact of a Subdomain Takeover

What harm could a subdomain takeover bring to your organization? Well, the impact mainly depends on three factors:

The nature of the third-party service (if any) that the vulnerable subdomain points to. Does the vendor offer little to no customization, or does it allow you to modify the style of the landing page via custom JavaScript or CSS code? Does it restrict you to serving static content, or is it a full-blown platform-as-a-service (PaaS) offering on which you can deploy a Web server?

The purpose and popularity of the vulnerable subdomain. What was the subdomain used for before becoming vulnerable? Was it used to simply host API documentation or was it instead used to authenticate users? Is the subdomain still receiving traffic? Is the subdomain name long and obscure (e.g., exctxzzxxp09.test.example.org ) or short and simple and, thus, unlikely to raise suspicion (e.g., auth.example.org )?

The trust relationship that the organization’s other Web assets have with the vulnerable subdomain. Would example.org blindly trust requests originating from the vulnerable subdomain? Would it accept to share sensitive data with that subdomain? Would it accept to load and execute JavaScript code hosted on that subdomain?

Now that you have a better idea of what factors into the impact of a subdomain takeover, let’s see how a malicious actor might exploit one.

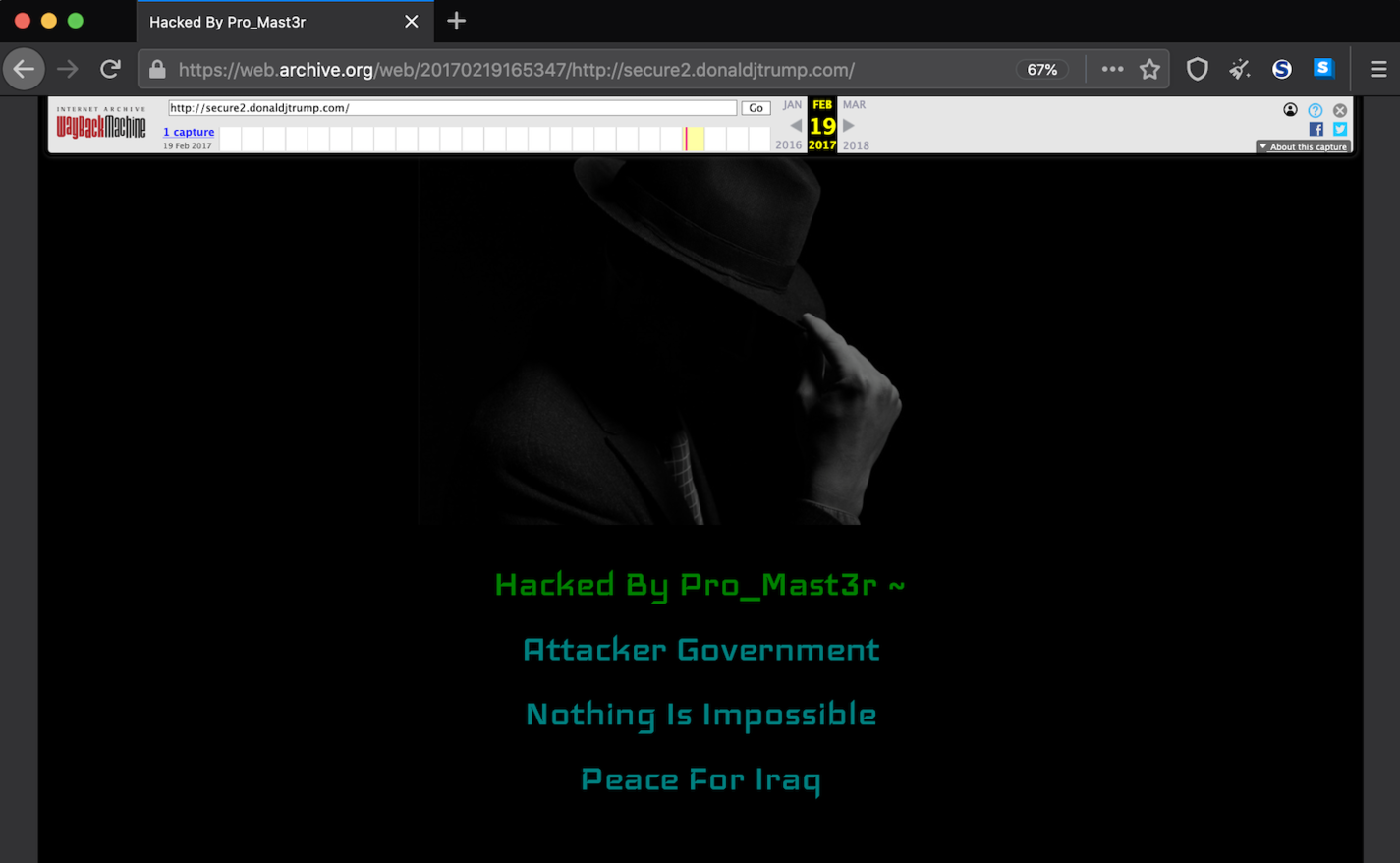

Defacement

Although the issue was quickly resolved, the offending page was captured and persists in the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine to this day. This incident arguably was neither the first nor the last cause for embarrassment for Trump, and it certainly did not prevent him from winning the 2016 presidency—as he was already in office at the time. However, I’m sure you can imagine how a defacement, possibly consisting of more offensive content than Trump’s hacker used, could harm your organization’s reputation.

Phishing

Another obvious way to exploit a subdomain vulnerable to takeover is phishing. Most phishing sites masquerading as a legitimate site (e.g., payments.example.org ) usually do not survive close scrutiny of the browser’s address bar because phishers typically have no other option than to host them on a lookalike domain (e.g., payments.exarnple.org ). Not so with a subdomain takeover! In fact, a subdomain takeover is the perfect spot for running a phishing campaign. After all, if the domain name example.org is trustworthy, then one would assume that any subdomain of example.org is also trustworthy, right?

Thanks to a subdomain takeover, phishers can readily leverage the reputation of the legitimate domain name to lure unsuspecting victims to it and elicit sensitive information (e.g., account credentials, personally identifiable information, and payment details) from them. Even tech-savvy visitors are likely to fall for the subterfuge.

In some cases, attackers may even be able to obtain and install a valid TLS certificate for the vulnerable subdomain to serve their phishing site over HTTPS; and, sad to say, many people (including Europol representatives, who should know better), still view the use of HTTPS as a reliable indicator for trustworthiness of the server on the other end of the connection.

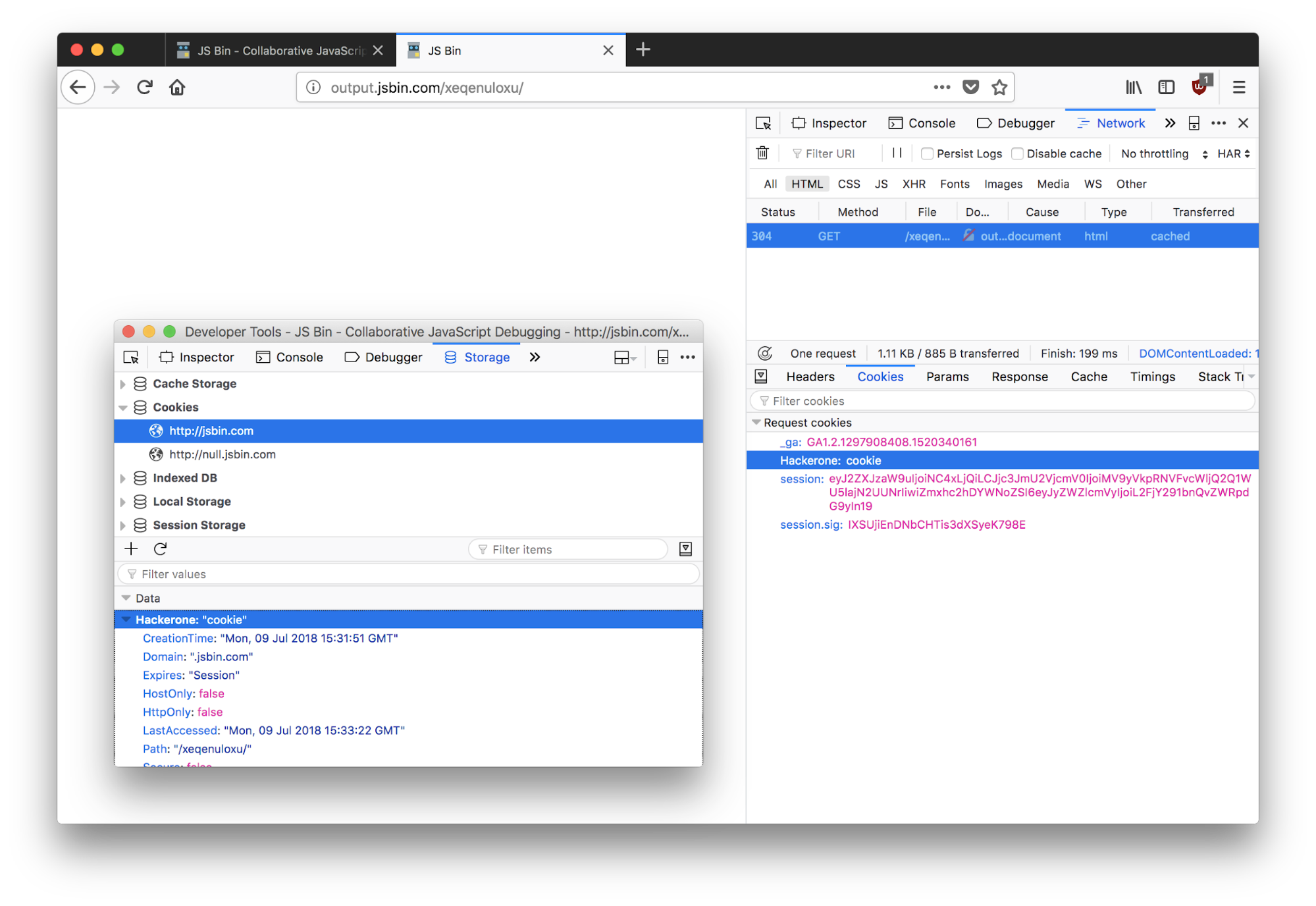

Stealing Broadly Scoped Cookies

Run-of-the-mill phishing typically requires some gullibility and user interaction (beyond navigating to the malicious site) from the victim. A subdomain takeover is more powerful, though, as it may enable an attacker to steal sensitive cookies simply by the victim visiting the attacker’s site.

Cookies have a Domain attribute, which determines where browsers are allowed to send them in HTTP requests. For instance, if a cookie is set from example.org with that hostname as the value of its Domain attribute, browsers will attach it to all HTTP requests sent to example.org or any subdomain thereof. Some sites, in a questionnable approach to implementing Single-Sign-On (SSO) authentication across all of their subdomains, set the Domain attribute of their session-identifying cookies to their root domain ( example.org ).

Now picture a malicious actor who has taken control over a subdomain and deploys their own malicious server there, which is set up to log all HTTP requests. By luring authenticated users to the compromised subdomain, the attacker will be able to harvest cookies scoped at the root domain simply by inspecting the server logs!

If session-identifying cookies are scoped this way, the attacker will be able to hijack user sessions and, perhaps, even take over user accounts.

Note that security cookie attributes cannot protect users who happen to visit the compromised subdomain. In particular,

Cross-Site Request Forgery

Cross-site request forgery (CSRF) is an attack that forces an end user to execute unwanted actions on a web application in which [he or she is] currently authenticated.

Let’s take a social network as an example. A CSRF attacker may perform sensitive actions, such as

all on behalf of the victim but against his or her will.

The SameSite cookie attribute was introduced to protect users against such cross-site attacks, but few organizations are taking full advantage of it. Thus, CSRF remains a risk wherever cookie-based authentication is used.

One possible mitigation against CSRF is to check the source origin of state-changing requests against a list of trusted origins. The Origin request header, when present, provides this information in a reliable fashion (more so than the Referer header does), because altering this header programmatically is simply not allowed by modern browsers. Many sites therefore rely on an origin-header check to decide whether to reject or accept a cross-site state-changing request.

Abusing Overtrusting CORS-Aware Servers

Malicious state-changing requests are not the only type of cross-site attacks you should be wary of, as attackers may also leverage cross-site requests to exfiltrate sensitive data. The same-origin policy (SOP), arguably the pillar of browser security, normally prevents such attacks.

Defeating a Permissive Content Security Policy

Recommendations

Now that you’re familiar with subdomain takeovers, here are a few things you can do to prevent them:

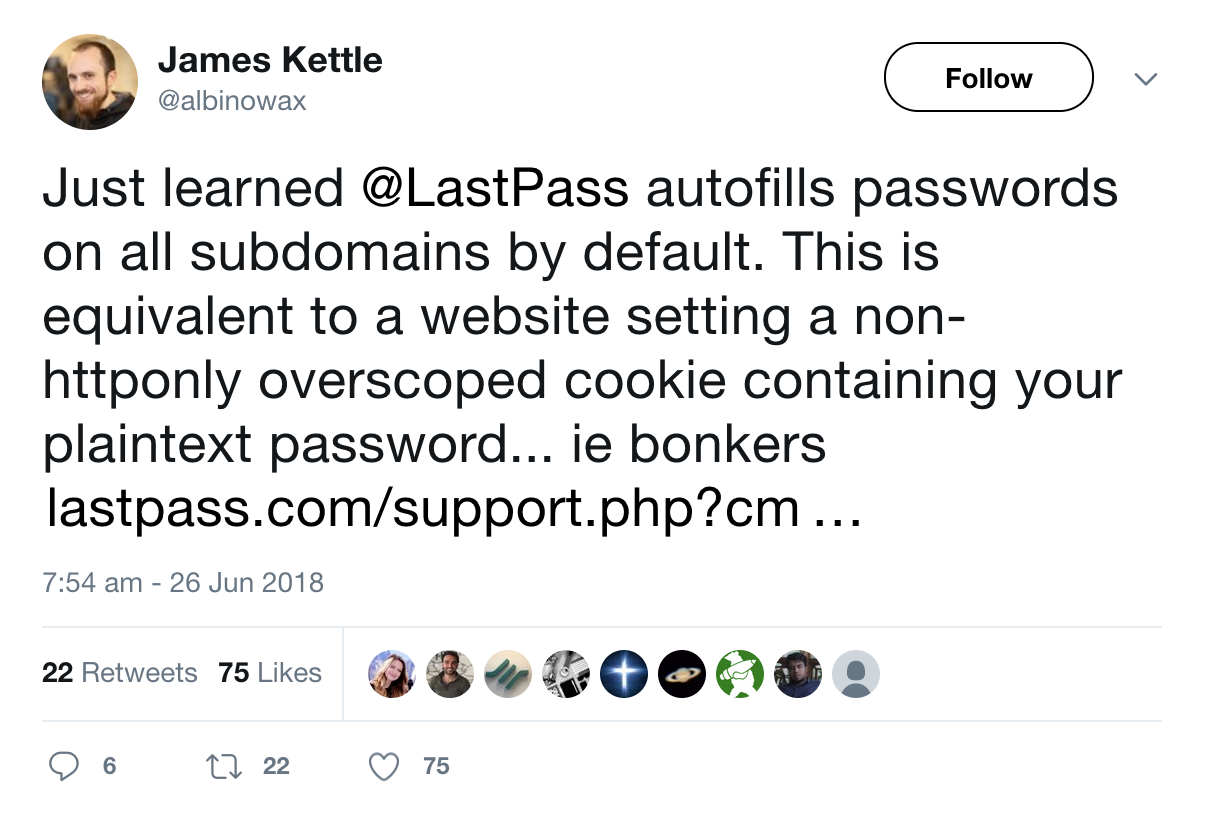

Select vendors wisely. Heed the words of James Kettle (Director of Research at PortSwigger):

Many companies have subdomains pointing to applications hosted by third parties with awful security practices.

Don’t be one of them. Treat every third-party service as you should any dependency: a liability. When shopping for a third-party solution that lets you point your subdomain to it, check whether the vendor protects its clients against subdomain takeover. Effective defense mechanisms include the following:

Close the attack window. Ethical hacker Edwin Foudil, in his can-i-take-over-xyz repository on GitHub, maintains a list of vendors that fail to protect their clients against subdomain takeover. If you decide to use any of these solutions, you have to be a bit more careful about the order in which you do things. Make sure to do the following:

This will effectively close the window during which you’re vulnerable to subdomain takeover.

Conclusion

I hope reading this post has raised your awareness of the risks associated with subdomain takeovers. Of course, this post only scratches the surface. Subdomain takeovers can be involved in other, more complex attacks. Moreover, some advanced forms of subdomain takeover involve DNS records other than CNAMEs.

If you would like to dig deeper, I recommend perusing Patrik Hudak’s blog, which goes into much more detail about the mechanics and impacts of subdomain takeover than this post does. HackerOne’s feed of disclosed bug-bounty reports is also an excellent resource on the topic.

Now, go audit your DNS records, be picky about vendors, and beware of subdomain takeovers!

Honeybadger has your back when it counts. We’re the only error tracker that combines exception monitoring, uptime monitoring, and cron monitoring into a single, simple to use platform.

Our mission: to tame production and make you a better, more productive developer. Learn more

Julien Cretel

Julien is a freelance software developer, security researcher, and Golang trainer. From the comfort of the French countryside, he works mostly remotely with clients all over the world. When he’s not writing code or hunting for bugs, he enjoys cooking, gardening, and playing and (re-playing) Cuphead.

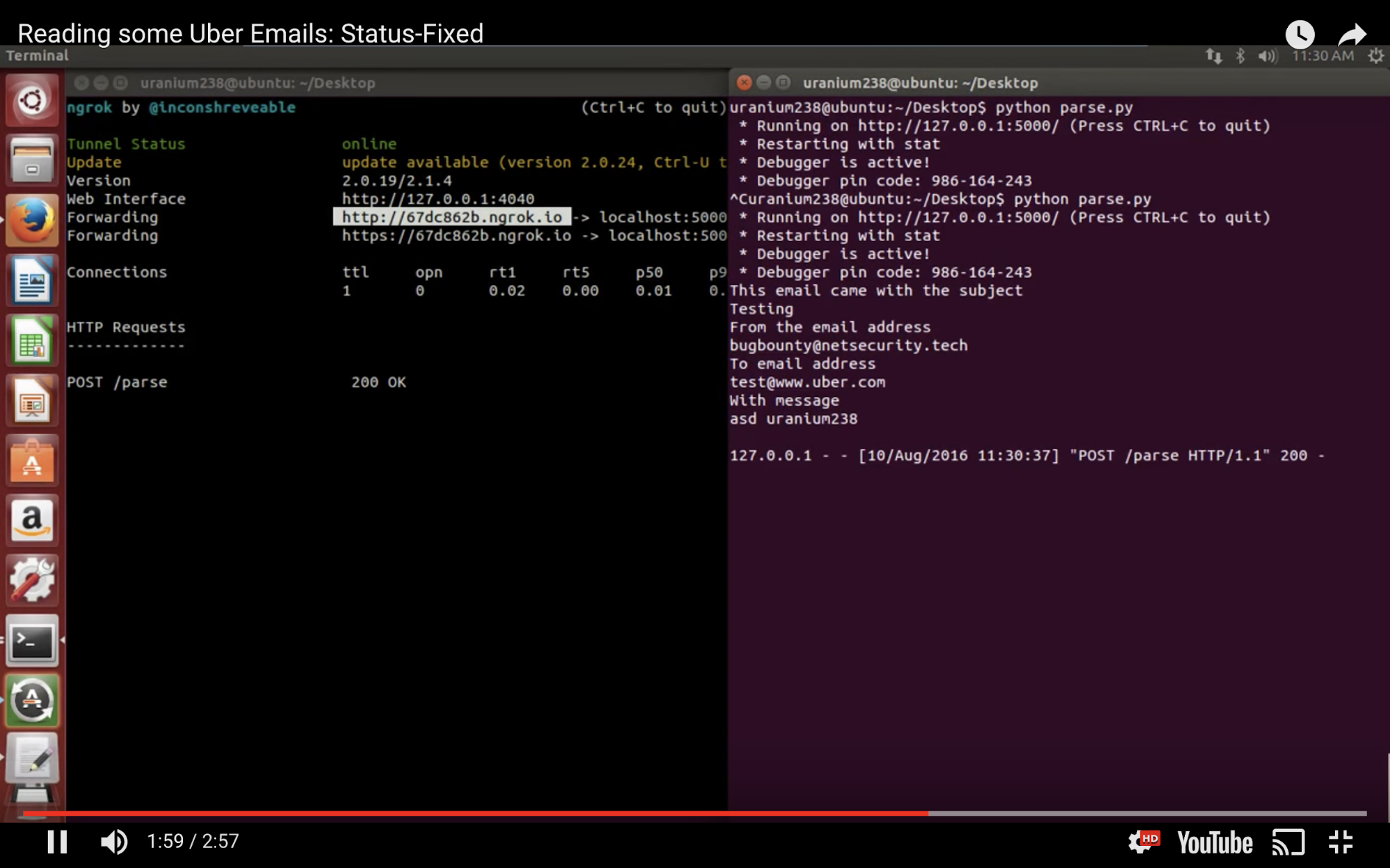

A Guide To Subdomain Takeovers

HackerOne’s Hacktivity feed — a curated feed of publicly-disclosed reports — has seen its fair share of subdomain takeover reports. Since Detectify’s fantastic series on subdomain takeovers, the bug bounty industry has seen a rapid influx of reports concerning this type of issue. The basic premise of a subdomain takeover is a host that points to a particular service not currently in use, which an adversary can use to serve content on the vulnerable subdomain by setting up an account on the third-party service. As a hacker and a security analyst, I deal with this type of issue on a daily basis. My goal today is to create an overall guide to understanding, finding, exploiting, and reporting subdomain misconfigurations. This article assumes that the reader has a basic understanding of the Domain Name System (DNS) and knows how to set up a subdomain.

Introduction to subdomain takeovers

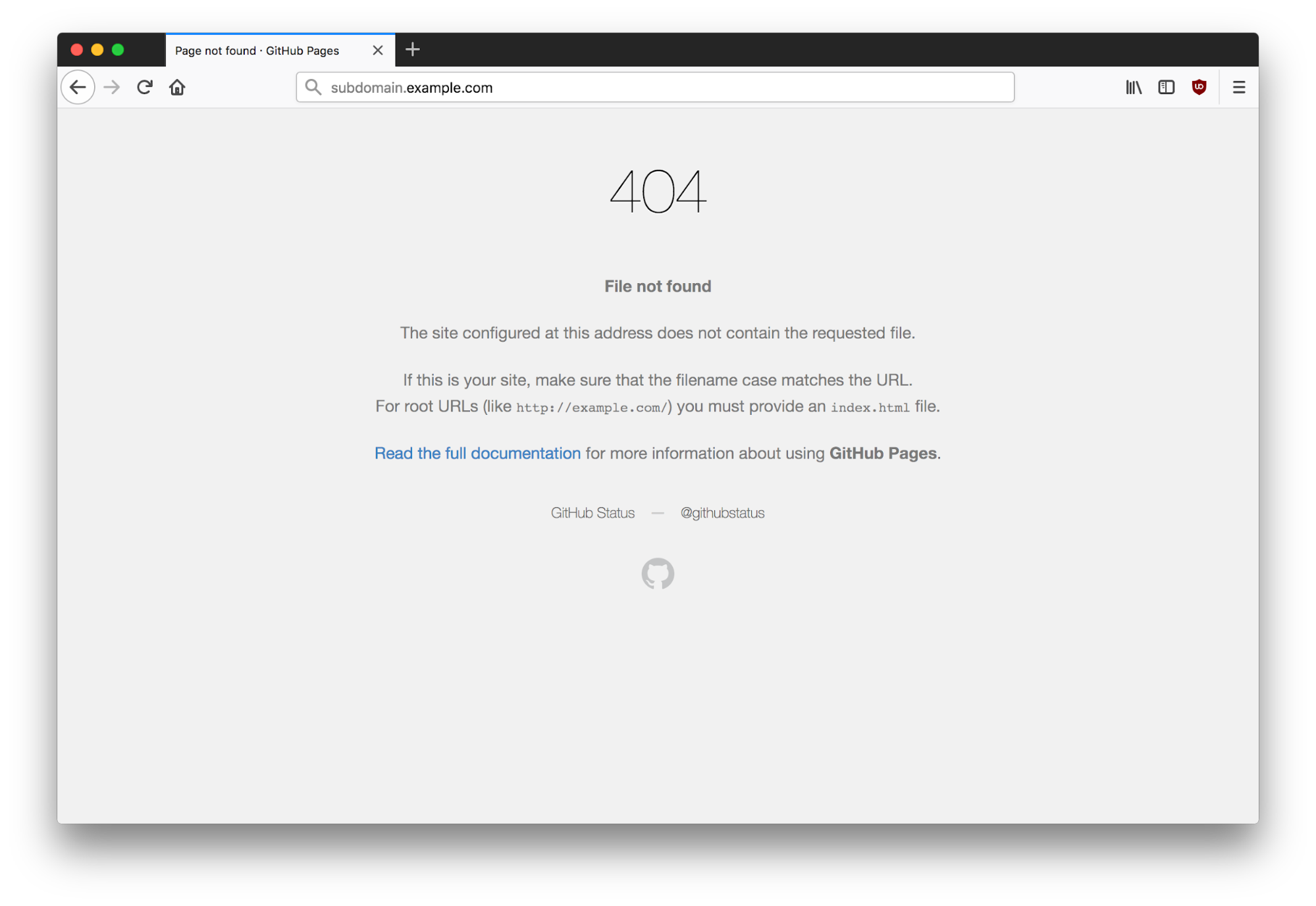

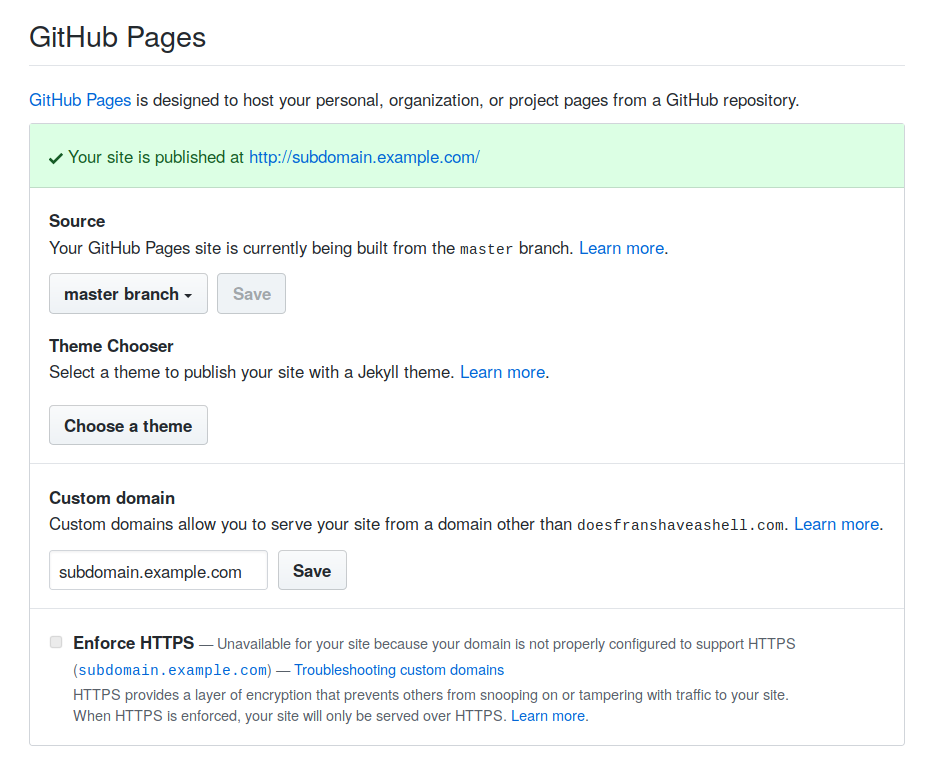

| $ host subdomain.example.com subdomain.example.com has address 192.30.252.153 subdomain.example.com has address 192.30.252.154 $ whois 192.30.252.153 | grep «OrgName» OrgName: GitHub, Inc. |

Most hackers’ senses start tingling at this point. This 404 page indicates that no content is being served under the top-level directory and that we should attempt to add this subdomain to our personal GitHub repository. Please note that this does not indicate that a takeover is possible on all applications. Some application types require you to check both HTTP and HTTPS responses for takeovers and others may not be vulnerable at all.

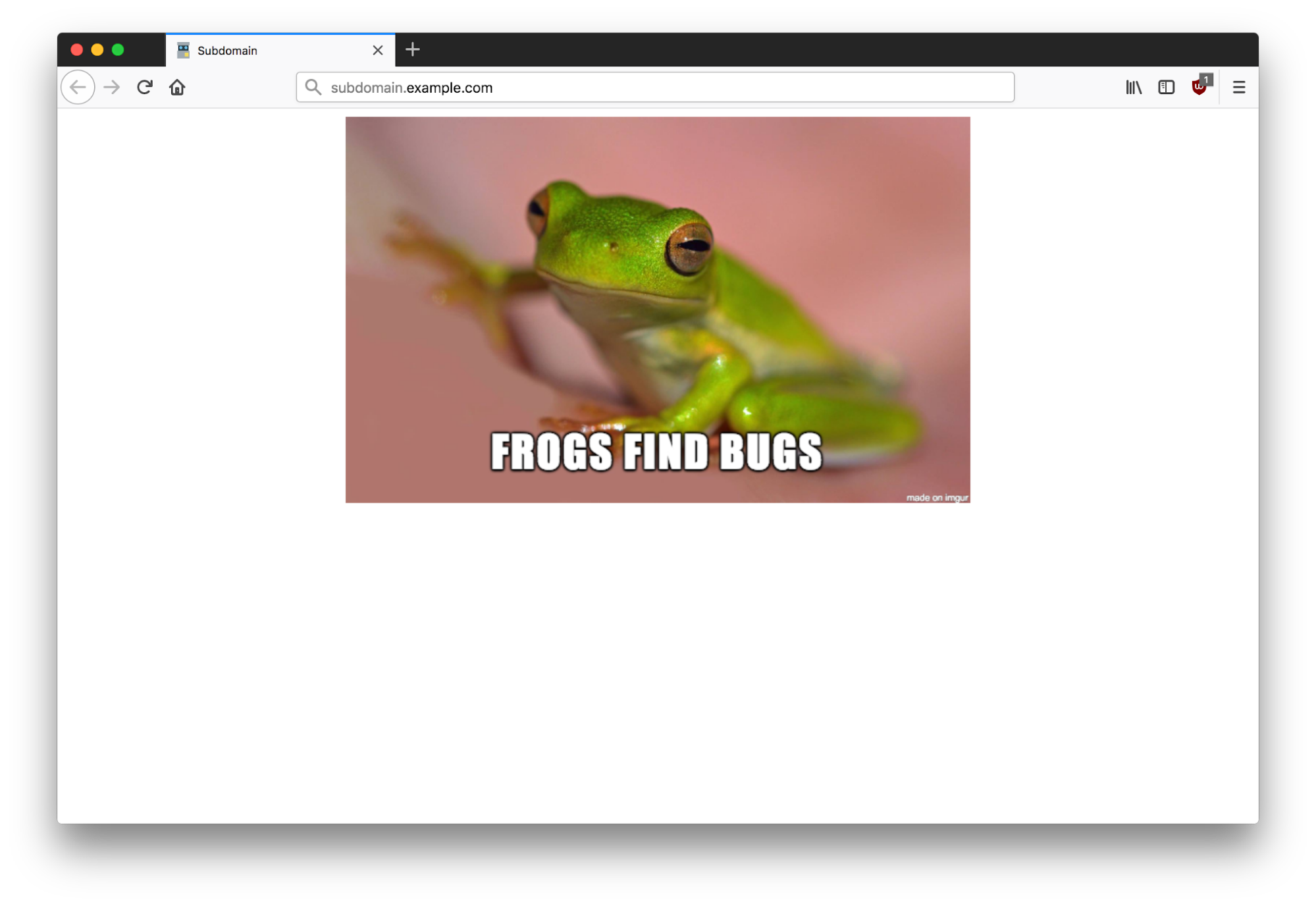

Once the custom subdomain has been added to our GitHub project, we can see that the contents of the repository are served on subdomain.example.com — we have successfully claimed the subdomain. For demonstration purposes, the index page now displays a picture of a frog.

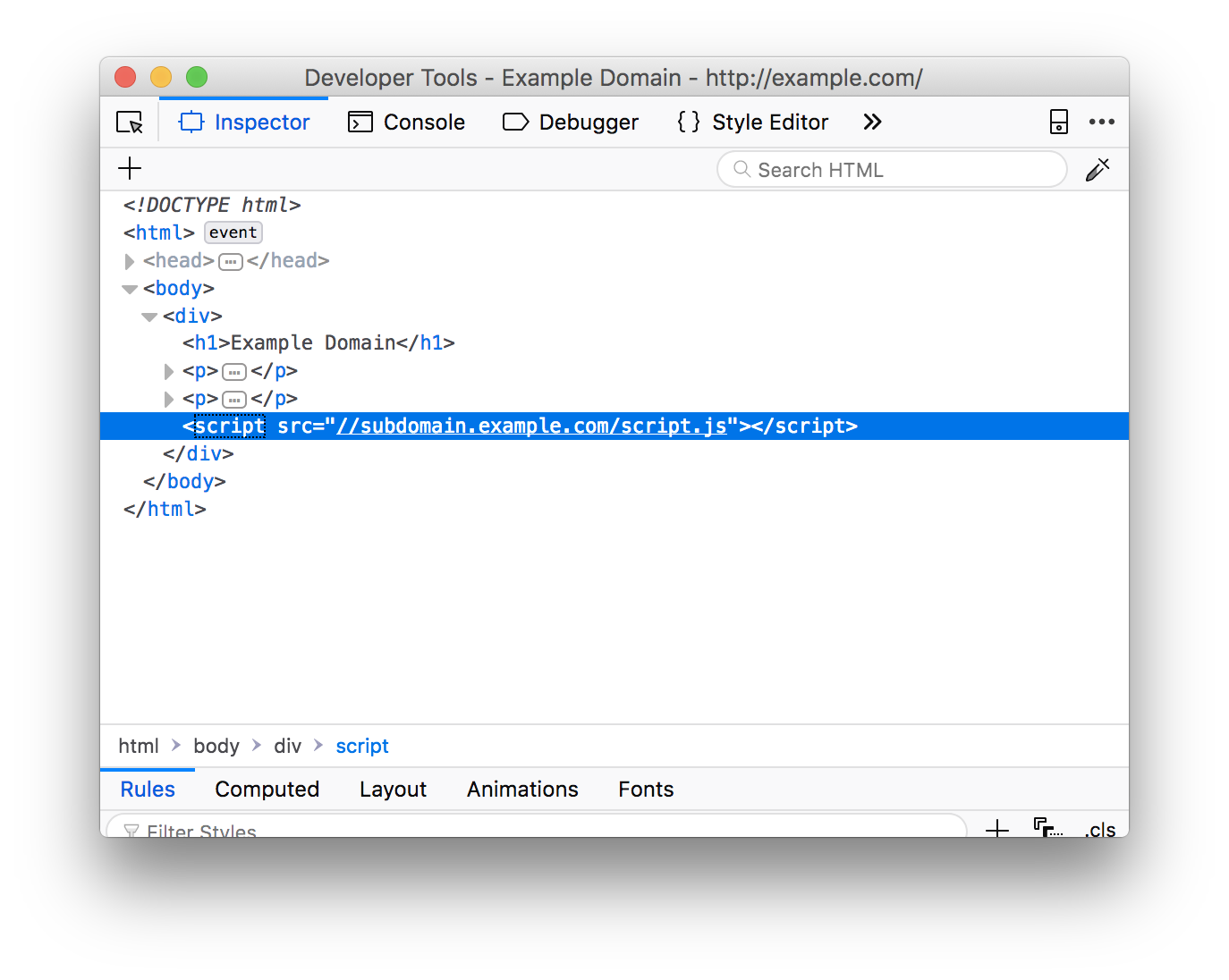

Second-order subdomain takeovers

Second-order subdomain takeovers, what I like to refer to as «broken link hijacking», are vulnerable subdomains which do not necessarily belong to the target but are used to serve content on the target’s website. This means that a resource is being imported on the target page, for example, via a blob of JavaScript and the hacker can claim the subdomain from which the resource is being imported. Hijacking a host that is used somewhere on the page can ultimately lead to stored cross-site scripting, since the adversary can load arbitrary client-side code on the target page. The reason why I wanted to list this issue in this guide, is to highlight the fact that, as a hacker, I do not want to only restrict myself to subdomains on the target host. You can easily expand your scope by inspecting source code and mapping out all the hosts that the target relies on.

This is also the reason why, if you manage to hijack a subdomain, it is worth investing time to see if any pages import assets from your subdomain.

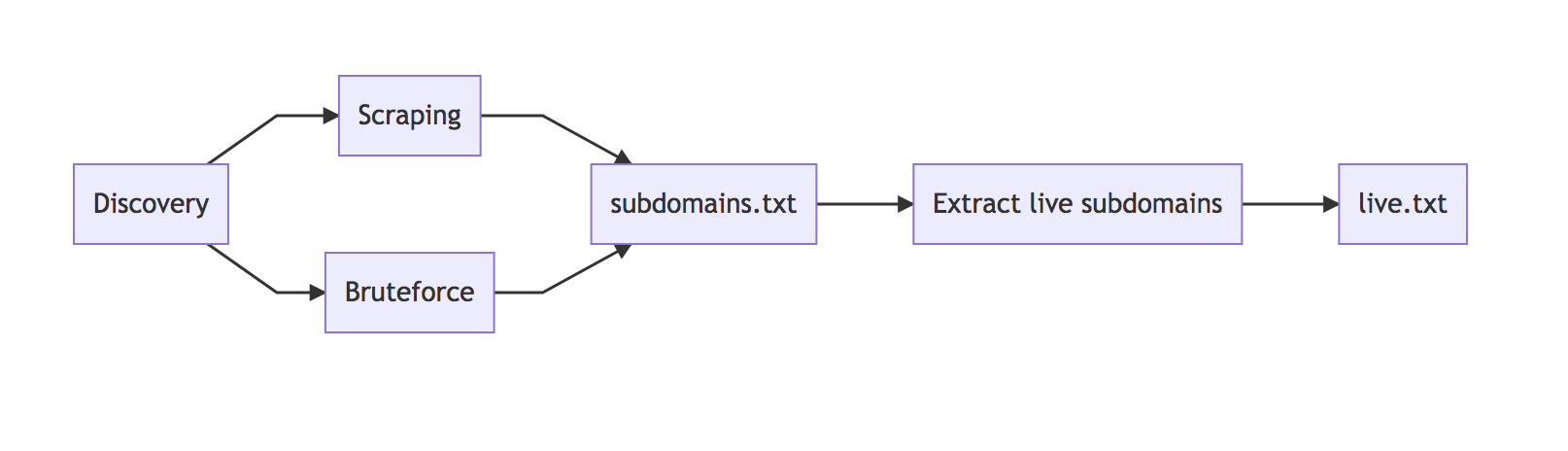

Subdomain enumeration and discovery

Now that we have a high-level overview of what it takes to serve content on a misconfigured subdomain, the next step is to grasp the huge variety of techniques, tricks, and tools used to find vulnerable subdomains.

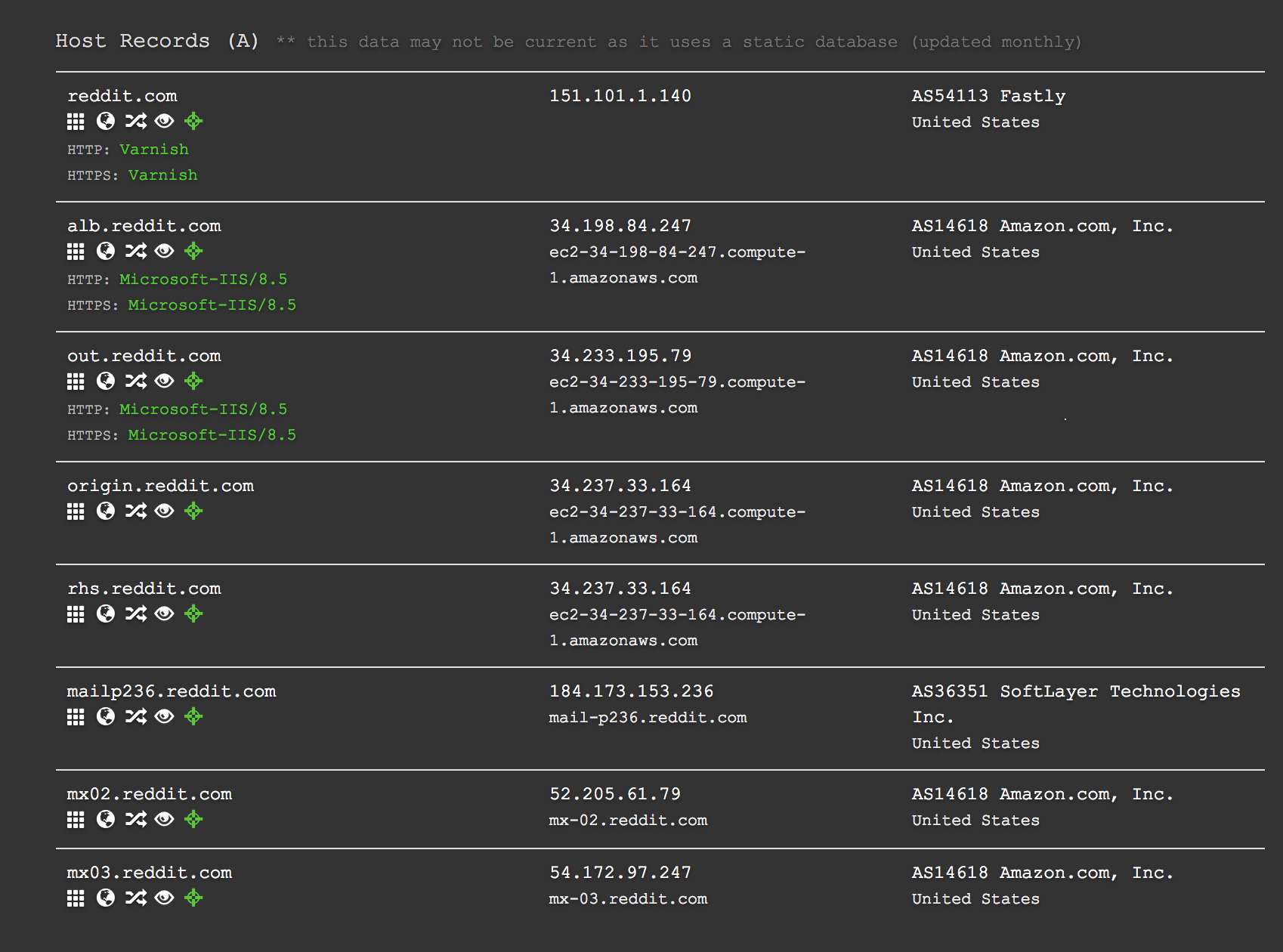

Before diving right in, we must first differentiate between scraping and brute forcing, as both of these processes can help you discover subdomains, but can have different results. Scraping is a passive reconnaissance technique whereby one uses external services and sources to gather subdomains belonging to a specific host. Some services, such as DNS Dumpster and VirusTotal, index subdomains that have been crawled in the past allowing you to collect and sort the results quickly without much effort.

Results for subdomains belonging to reddit.com on DNS Dumpster.

Scraping does not only consist of using indexing pages, remember to check the target’s GIT repositories, Content Security Policy headers, source code, issue trackers, etc. The list of sources is endless, and I constantly discover new methods for increasing my results. Often you will find that the more peculiar your technique is, the more likely you will end up finding something that nobody else has come across; so be creative and test your ideas in practice against vulnerability disclosure programmes.

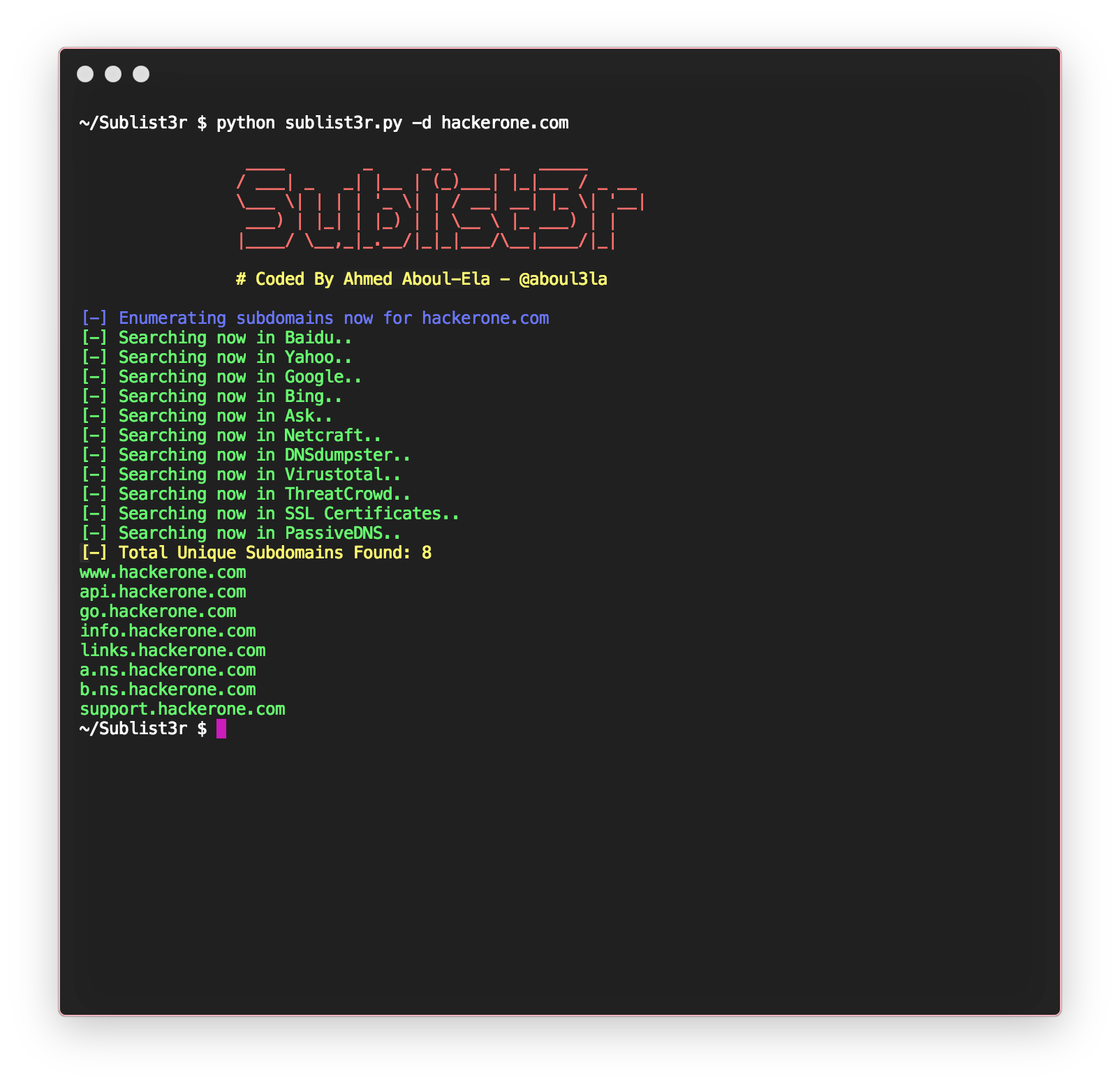

Sublist3r by Ahmed Aboul-Ela is arguably the simplest subdomain scraping tool that comes to mind. This light-weight Python script gathers subdomains from numerous search engines, SSL certificates, and websites such as DNS Dumpster. The set-up process on my personal machine was as straightforward as:

When brute forcing subdomains, the hacker iterates through a wordlist and based on the response can determine whether or not the host is valid. Please note, that it is very important to always check if the target has a wildcard enabled, otherwise you will end up with a lot of false-positives. Wildcards simply mean that all subdomains will return a response which skews your results. You can easily detect wildcards by requesting a seemingly random hostname that the target most probably has not set up.

| $ host randomifje8z193hf8jafvh7g4q79gh274.example.com |

For the best results while brute forcing subdomains, I suggest creating your own personal wordlist with terms that you have come across in the past or that are commonly linked to services that you are interested in. For example, I often find myself looking for hosts containing the keywords «jira» and «git» because I sometimes find vulnerable Atlassian Jira and GIT instances.

If you are planning on brute forcing subdomains, I highly recommend taking a look at Jason Haddix’s word list. Jason went to all the trouble of merging lists from subdomain discovery tools into one extensive list.

Fingerprinting

To increase your results when it comes to finding subdomains, no matter if you are scraping or brute forcing, one can use a technique called fingerprinting. Fingerprinting allows you to create a custom word list for your target and can reveal assets belonging to the target that you would not find using a generic word list.

Notable tools

There is a wide variety of tools out there for subdomain takeovers. This section contains some notable ones that have not been mentioned so far.

Altdns

In order to recursively brute force subdomains, take a look at Shubham Shah’s Altdns script. Running your custom word list after fingerprinting a target through Altdns can be extremely rewarding. I like to use Altdns to generate word lists to then run through other tools.

Commonspeak

Yet another tool by Shubham, Commonspeak is a tool to generate word lists using Google’s BigQuery. The goal is to generate word lists that reflect current trends, which is particularly important in a day and age where technology is rapidly evolving. It is worth reading https://pentester.io/commonspeak-bigquery-wordlists/ if you want to get a better understanding of how this tool works and where it gathers keywords from.

SubFinder

A tool that combines both scraping and brute forcing beautifully is SubFinder. I have found myself using SubFinder more than Sublist3r now as my general-purpose subdomain discovery tool. In order to get better results, make sure to include API keys for the various services that SubFinder scrapes to find subdomains.

Massdns

Massdns is a blazing fast subdomain enumeration tool. What would take a quarter of an hour with some tools, Massdns can complete in a minute. Please note, if you are planning on running Massdns, make sure you provide it with a list of valid resolvers. Take a look at https://public-dns.info/nameservers.txt, play around with the resolvers, and see which ones return the best results. If you do not update your list of resolvers, you will end up with a lot of false-positives.

Automating your workflow

When hunting for subdomain takeovers, automation is key. The top bug bounty hunters constantly monitor targets for changes and continuously have an eye on every single subdomain that they can find. For this guide, I do not believe it is necessary to focus on monitoring setups. Instead, I want to stick to simple tricks that can save you time and can be easily automated.

The first task that I love automating is filtering out live subdomains from a list of hosts. When scraping for subdomains, some results will be outdated and no longer reachable; therefore, we need to determine which hosts are live. Please keep in mind, as we will see later, just because a host does not resolve, does not necessarily mean it cannot be hijacked. This task can easily be accomplished by using the host command — a subdomain that is no longer live will return an error.